Nord Stream Studies

June 18, 2022

In 1969, a gas field with an estimated 805.3×109 cubic meters of natural gas was discovered by Soviet geologists in the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Region in West Siberia. The gas field, located in an Arctic area populated by the indigenous Nenets people, who had for centuries been subjected to colonial exploitation by the Russian settlers, was named Yuzhno-Russkoye (that is, ‘Southern Russian’). Yuzhno-Russkoye was one of the numerous gas reserves that had been discovered in Siberia at the time, making the USSR an owner of the largest fossil fuel deposits on Earth.

On February 1st, 1970, the Federative Republic of Germany signed a deal with the Soviet Union enabling the export of German pipes needed for the construction of a transcontinental gas pipeline that would connect Western Siberia and Western Germany. In Russian historiography, this contract is referred to as ‘the deal of the century’. Over the course of 1970-80s, this deal allowed for the construction of a network of gas pipelines that transformed the Soviet Union into a major exporter of fossil fuels to Western Europe.

The piercing of the Iron Curtain by Soviet gas infrastructure had been fiercely opposed by the US government, who warned their allies about the threat of weaponization of Soviet fossil fuel exports, and argued against increased German dependence on Soviet natural gas[1]. The German response relied on a belief in the transformative power of market relations on the centralized economy of the USSR. The advocates of the project in Germany calculated that the promise of long-term ultra-lucrative fossil fuel exports would not only turn the Soviet Union into a more reliable trade and security partner, but might also tempt it to abandon its planned economy and opt for capitalist market relations.

By the end of the 1980s, these calculations proved to be correct in the short term. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, Soviet elites embarked on a top-down dissolution of the socialist rule in the USSR, their main objective being the privatization of the vast industrial resources left behind by the Soviet regime (with the infrastructures for extraction and transportation of fossil fuels the most lucrative prize). This top-down dissolution, however, had not been able to account for the growing decolonial movements in the non-Russian republics of the Soviet Union, which resulted in Russia’s loss of a great deal of its colonies after the collapse of the USSR in 1991.

The post-colonial relationship between Russia and the new East European states had been largely defined economically by the subterranean infrastructures for fossil fuel transit, which now carried Russian oil and gas to Western Europe via the territories of Ukraine and Belarus. Its status as a fossil fuel transit zone allowed Ukraine to collect revenues for the use of a segment of pipeline network stretching under its territory, but it also turned its economy into an appendage of its ex-colonizer’s extractionist industry.

In the meantime, the Russian Federation had started to experience the full-scale effects of the extractionist mode of organizing its economy, such as the outsized influence of the security apparatus and the erosion of democratic procedures. Putinism emerged as a mode of political governance due to its ability to concentrate exorbitant profits from fossil fuel exports in the hands of the ruling few[2]. The wealth created by those exports would be used to revert the perceived loss of Russia’s imperial grandeur. Those fossil fuel networks that were instrumental in dismantling Soviet socialism by its Western trading partners would now be weaponized in Russia’s dismantling of the post-Cold War European order.

In 1997, the first studies for an undersea natural gas pipeline in the Baltic had been launched, paving the way for the Nord Stream project meant to connect Russia and Germany directly under the Baltic seabed, bypassing transit countries like Ukraine, Belarus and Poland. The Nord Stream’s route would lie along the way of Medieval and early Modern Hanseatic marine trade routes. The Yuzhno-Russkoye gas field would become the primary source of natural gas flowing through the Nord Stream pipeline.

In December 2005, weeks after Germany’s ex-chancellor Gerhard Schroeder’s departure from his post, he was appointed a leader of Nord Stream’s shareholder committee. In October 2012, Russian gas deliveries over the new pipeline were launched. In early September 2015 – as Russia’s war in Ukrainian Donbas had already been raging for over a year – a deal on the construction of Nord Stream II was reached between Russia and Germany[3]. Completion of this additional pipeline would totally phase out the need to transit Russian gas via Ukraine, effectively rendering its geopolitical role in Europe obsolete. The certification of a fully completed Nord Stream II pipeline was frozen by the German government on February 22, 2022 – one day after a de facto declaration of Russia’s war on Ukraine, and two days before an actual invasion.

During the heated debate around the construction of Nord Stream 2, the geopolitical arguments had mostly overshadowed the ecological concerns regarding the pipeline that would have emitted an additional 55 billion cubic meters of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere annually. The role of the German government in pursuing the interests of Russian and German fossil fuel lobbies to the detriment of its own energy transition agenda should now be scrutinized as the war rages and the climate crisis intensifies.

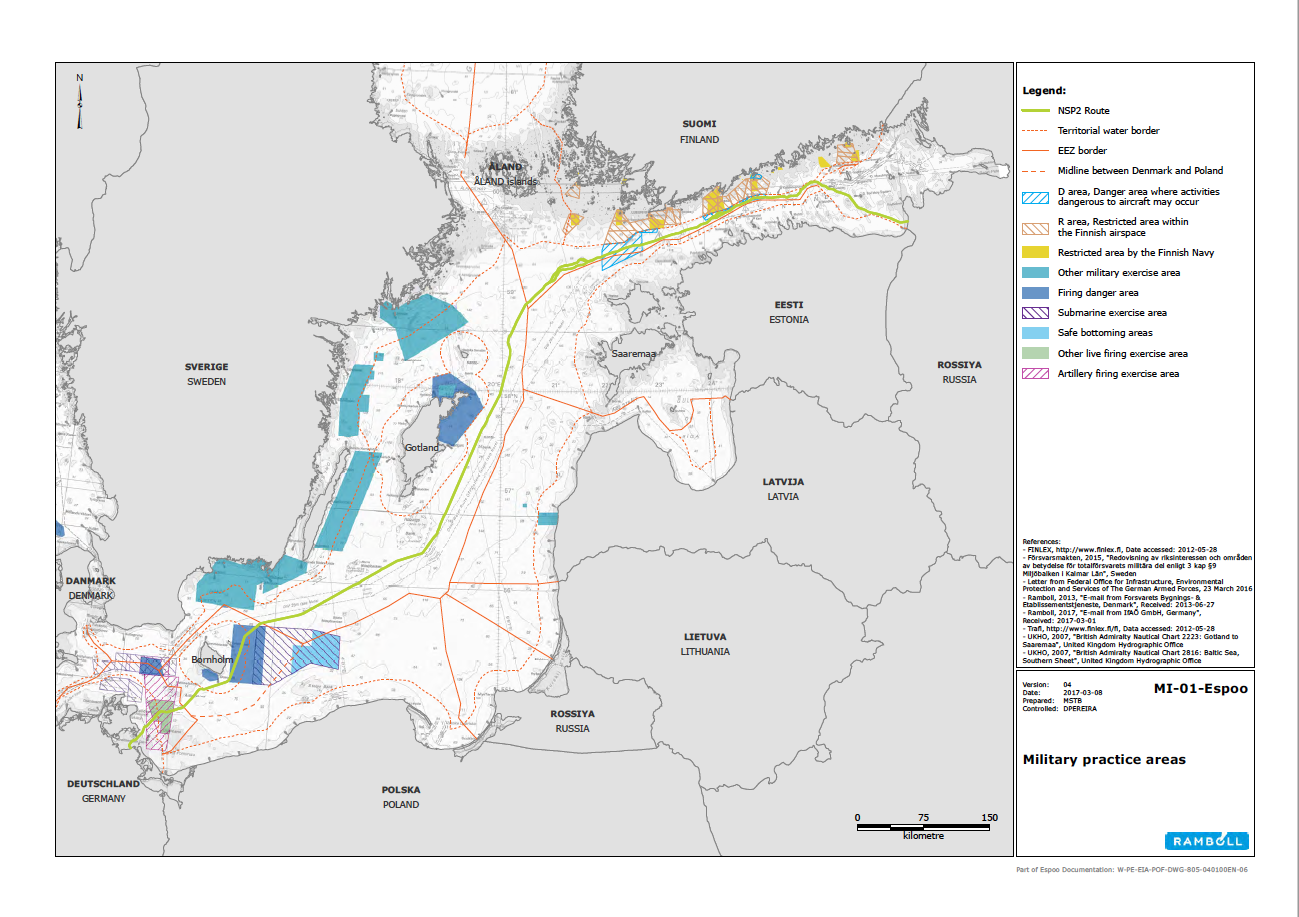

The maps illustrating this text are taken from ESPOO Atlas (the Nord Stream 2 environmental impact assessment documentation under the Espoo convention).

[1] This dispute was a subject of an early work by the current US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken, Ally Versus Ally: America, Europe and the Siberian Pipeline Crisis (1987).

[2] See for instance: Alexander Etkind, Nature's Evil: A Cultural History of Natural Resources, Polity Press, 2021

[3]https://web.archive.org/web/20150619181351/http://uk.reuters.com/article/2015/06/19/us-gazprom-shell-exclusive-idUSKBN0OZ0IQ20150619